- A recent study reveals that 71.7% of miners at artisanal gold mining sites in Cameroon show mercury levels at concentrations above the limit recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

- Mercury use in artisanal mining has nevertheless been banned by the Cameroonian government since 2019 as hundreds of deaths occur yearly at mining sites.

- These fatalities result from gold mining’s uncontrolled development in Cameroon, where companies are continuously in conflict with communities and where national mining legislation has yet to come into force.

BATOURI, Cameroon – At Kambélé III, an artisanal mining site in the commune of Batouri, located 415 kilometers (268 miles) east of Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital, male, female, teenage, and child gold miners are already hard at work on a sunny Thursday morning.

Clothed in rags and without protection, they dig, comb, and excavate the gutted site across hectares of land as far as the eye can see. Some transport large quantities of soil and stone to grinding mills, whose whirling sound creates a deafening roar. On both sides of the site, archaic wooden facilities have been set up as laboratories and are used to refine ore and extract gold from it.

With his bare hands plunged in a copper basin, Saliou Hassana, a 17-year-old gold miner, constantly mixes its contents, a muddy and yellowish water containing gold particles. His meticulous work aims to extract the gold from the particles. After a few minutes of mixing, he obtains blackish sediments in which gold nuggets are buried.

As the final step to separate the treasure from the ore, Saliou uses a chemical substance carefully preserved in a piece of wool: mercury. The resulting 0.15 microns of gold is immediately sold to an eager collector for less than $7.58 (5,000 FCFA).

Saliou obtains the mercury from gold collectors on the black market. They discreetly sell small doses to gold miners, and for a capful three centimeters in diameter, the artisanal miner must pay up to $22.63 (15,000 FCFA). The collectors are vague about the quantities sold daily and even less forthcoming about where substance is sourced.

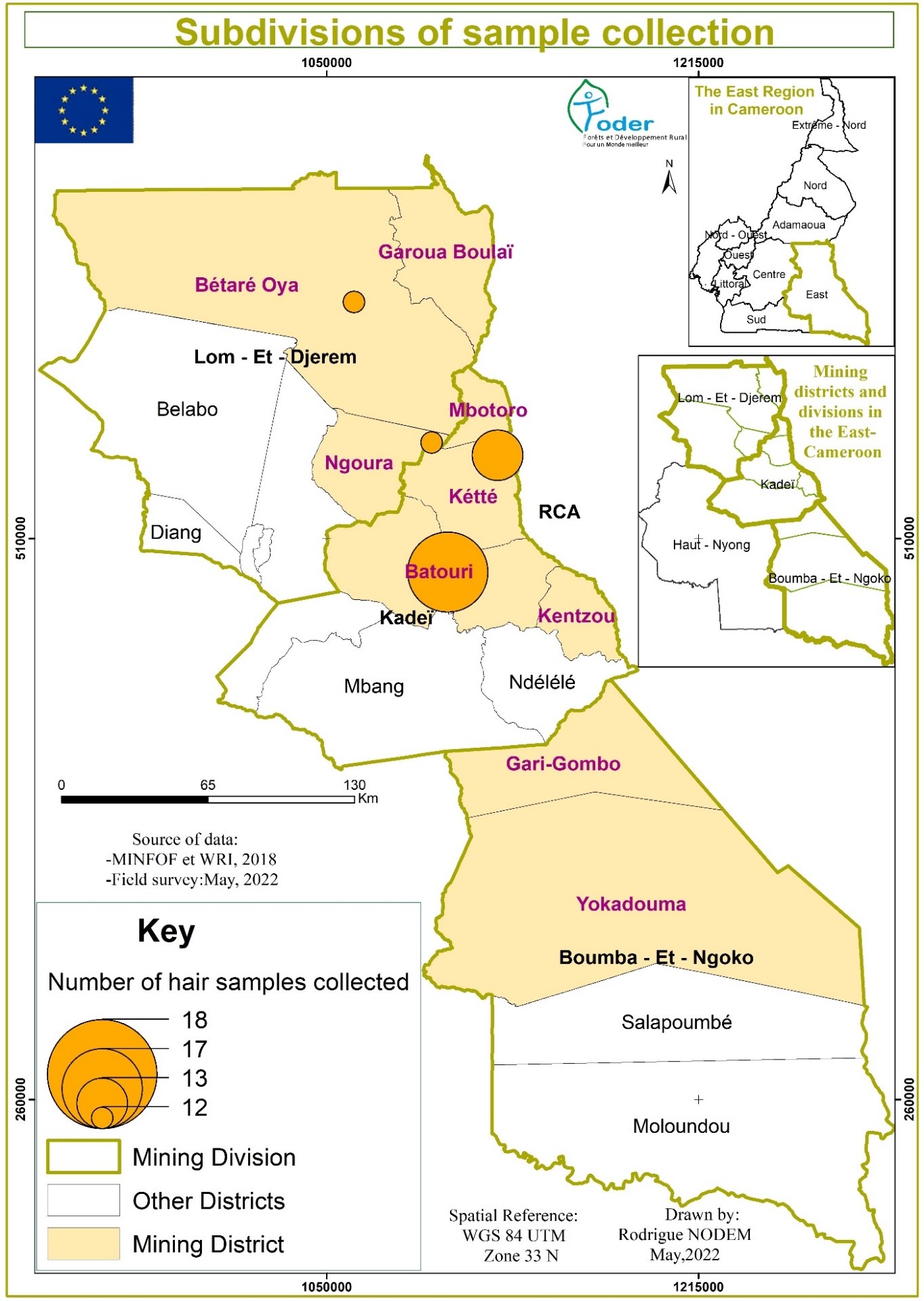

In October, the non-governmental organization FODER, which is committed to environmental and human rights issues, published an analysis of hair samples taken from 60 gold miners working in the communes of Batouri, Kette, Ngoura, and Bétaré-Oya.

The maximum, minimum, and mean concentrations of mercury found in their hair were 8.97 mg/kg, 0.78 mg/kg, and 2.1 mg/kg. The total mercury concentration was above the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended limit in 71.7% of the individuals sampled.

According to the study, most of these gold miners with high mercury levels were exposed to it between the ages of two and ten, which puts them at risk of acute mercury poisoning, says Dr. Ralph Obase Musono, a health and safety medical specialist who also served as a consultant for this study.

“It is important to clarify that where there is acute mercury poisoning, there is a risk of developing skin diseases. If a person has inhaled a large amount, they can develop pneumonia, but it depends on the context,” he explains.

“For example, in a pregnant woman exposed to mercury, the inhaled substance can spread to the placenta and block the oxygen flow to the baby, carrying a risk of miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, or birth defects. And in cases of long-term or chronic exposure to mercury, the miner can develop skin, brain, or liver cancer.”

According to a recent U.N. report, 2,058 metric tons of mercury is contaminating water, land, and air every year.

Earning inconsistent daily profits from artisanal gold mining and working in exacting conditions, Saliou, originally from the North Region, which had the second-highest concentration of the country’s poor at 20.1% in 2014, endangers his health using a substance that has been prohibited by the Ministry of Mines, Industry and Technological Development since August 2019.

But he has no knowledge of this.

“I wasn’t aware of the ban. Who banned its use?” he asks before telling Mongabay, “We have always used this here [Kambélé III] to find gold. Otherwise, how are we going to separate the gold from the rest?”

However, the government measure is rarely enforced. The sectoral ministry is conspicuously absent when it comes to monitoring the measure’s implementation.

“We try to track down the lawbreakers, but as our decentralized departments are understaffed, the administration’s control over this activity is slightly lacking,” admits Evelyne Ngo Nyeck, an executive officer at the National Brigade of Controls of Mining Activities at the Cameroonian Ministry of Mines.

Read more: U.N. report calls for the ban of mercury trade and its use in gold mining

Abandoned pits, artificial lakes

According to Justin Landry Chekoua, head of the Mining, Environment, Health and Society Phase 2 Project (ProMESS 2) at FODER, the study was partly motivated by the increased number of deaths recorded at mining sites in recent years.

“We wanted, beyond the deaths, to understand the root causes and dangers to which they are exposed to be able to discuss it with undisputed scientific data from this point forward,” he affirms.

Between 2014 and 2022, the NGO has already recorded 205 deaths at mining sites in the East and Adamawa Regions, the majority caused by the gaping, abandoned pits made by excavators in semi-mechanized artisanal mining.

In September 2021, FODER counted 703 pits at mining sites, including 139 artificial lakes on 93 hectares (230 acres) of land, into which these companies often discharge waste oils and hydrocarbons from mining. In violation of Cameroonian mining law, these pits are abandoned by the companies operating in these regions.

In 2016, the country adopted a new mining code, which specifies in Article 136 that operators have the responsibility to restore mining sites. Nevertheless, this provision is not respected as its entry into force remains conditional on Cameroonian President Paul Biya’s signature of its implementing decree, which has been awaited for six years.

As a result, mining activity in Cameroon is still governed by the old mining code adopted in 2001.

Mining companies, the majority of which are owned by foreign Chinese nationals, are thus taking advantage of this imbroglio, as demonstrated by cases of multifaceted human rights violations and their destruction of the ecosystem. They also use mercury and cyanide (another substance banned by the Ministry of Mines) in their activities.

Last June, the non-profit organization Centre for Environment and Development (CED) revealed that on average, 40 liters of mercury and cyanide are dumped into the waterways flowing through Kambélé III daily by a Chinese company.

The circumstances worsened to the point where, in July, Yakouba Djadaï, the Prefect of Kadey, the department to which Batouri is administratively linked, suspended nine companies operating in the commune, including six belonging to foreign Chinese nationals, before beginning restoration processes a month later.

One of the companies belonging to a national known as “Wang” is also accused of appropriating eight hectares (20 acres) of land belonging to village communities in Narke II (located five kilometers – 3 miles – from Batouri).

“Wang’s company crossed Kambélé III, ending up in Narke II in my territory. He destroyed all the plantations with his machines. We have lost our crops, and he has compensated us nothing. And yet no contract exists between the village and this gentleman,” says disillusioned Rosette Gomane, chief of the village.

Mongabay was unable to reach the party in question. Access to the company’s facilities in Kambélé II is blocked, guarded by men in plain clothes whom residents present as Cameroonian soldiers.

The village communities have nonetheless found significant support within civil society to help them regain their land. Three local organizations, including FODER, backed by the Cameroonian chapter of Transparency International, appealed to Prefect Yakouba Djadaï in August to denounce the destruction of agricultural plantations belonging to Narke II villagers.

The department’s central government representative told Mongabay, “As far as I know, there are no active mining operations in Narke II. When companies have violated people’s rights, I have reacted with a hard hand,” he answered.

In turn, he revealed that a project to build a weighing station in the village is in preparation and that the State will do everything in its power at that time to respect the land rights of the affected communities.

“It will be built on 300-square-meter site. If we find that there are people inhabiting areas on the site, we will compensate them before beginning work.”

Undeclared gold

In Cameroon, gold mining is developing chaotically and remains out of the government’s control. However, statistics from the Cameroonian Ministry of Mines show that gold is one of the most sought-after mineral substances by mining companies in the country.

By way of illustration, in 2020, a total of 37 exploration permits were issued to companies for semi-mechanized mining, 19 of which were for gold. However, there has been a decrease in semi-mechanized artisanal gold production from since 2019.

The CED has published the results of a recent investigation into the fraudulent practices plaguing the sector in which it laments that “not all of Cameroon’s gold production is declared, and producers are implementing active concealment strategies with the aim of evading taxation.”

The study also reveals that in 2018, gold from Cameroon was mainly imported by the United Arab Emirates and Germany.

This article was first published here on Mongabay’s French page on Mar. 30, 2022.

Banner image: Saliou Hassana, a 17-year-old gold miner, extracting and collecting gold nuggets using mercury at Kambélé III. Image © Yannick Kenné.

Find out more on the Mongabay podcast: An interview with Anuradha Mittal, Executive Director of the Oakland Institute, and Christian-Geraud Neema Byamungu, a Congolese researcher, on the impact of resource extraction on human rights and the environment in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Listen here:

Chinese companies criticized for mercury pollution in Cameroon

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This story first appeared on Mongabay

South Africa Today – Environment

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and Mongabay, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.