South Africa’s parliament is currently debating amendments to the Labour Relations Act that will change how workers can go on strike. For example, the amendments would require trade unions to hold secret ballots to decide on strike action and introduce a mechanism where strikes could be resolved through an advisory arbitration panel.

The Department of Labour has justified the proposed changes to strike legislation by arguing that they are prevalent, prolonged and increasingly violent. But a look at the data provided in the Department of Labour’s own industrial action annual reports reveals a different picture.

The data shows that strikes have not particularly increased over the last decade, tend to be resolved in under two weeks and that the vast majority occur peacefully.

So the justification used by the Department of Labour is not based on fact but on an ideological perspective that seeks to protect employers’ interests at the expense of workers.

Recently, even the International Monetary Fund has recognised that weakening unions by undermining the right to strike leads to declining wages and increasing inequality. Given that South Africa is among the most unequal countries in the world, lawmakers should be giving serious thought as to how they can protect the rights of workers and their right to strike.

Assessing the data

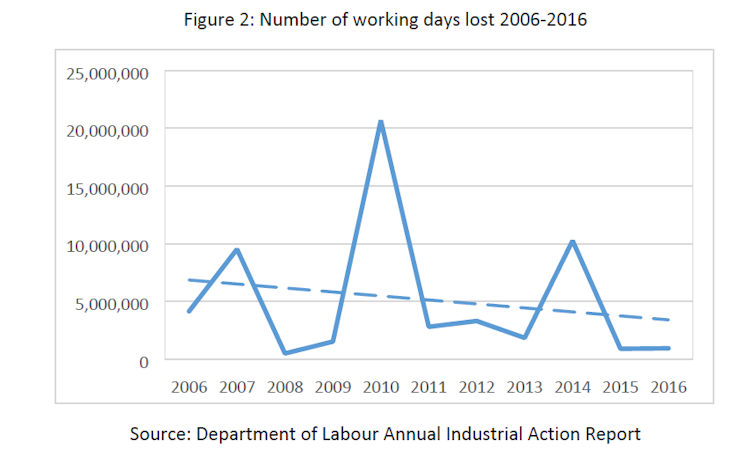

Over a ten year period there has been a slight increase in the number of work stoppages (see figure 1). But this is a very imprecise measure of industrial action as work stoppages vary in duration. It’s therefore more accurate to use the number of working days lost as an indicator of the intensity of industrial action.

Department of Labour Industrial Action Annual Reports

Looking at this data demonstrates that there have been years where the number of working days lost has been high – including during the 2010 public sector strike and the 2014 platinum strike. Overall, though, there has been a slight decline in the number of working days lost.

Department of Labour Annual Industrial Action Report

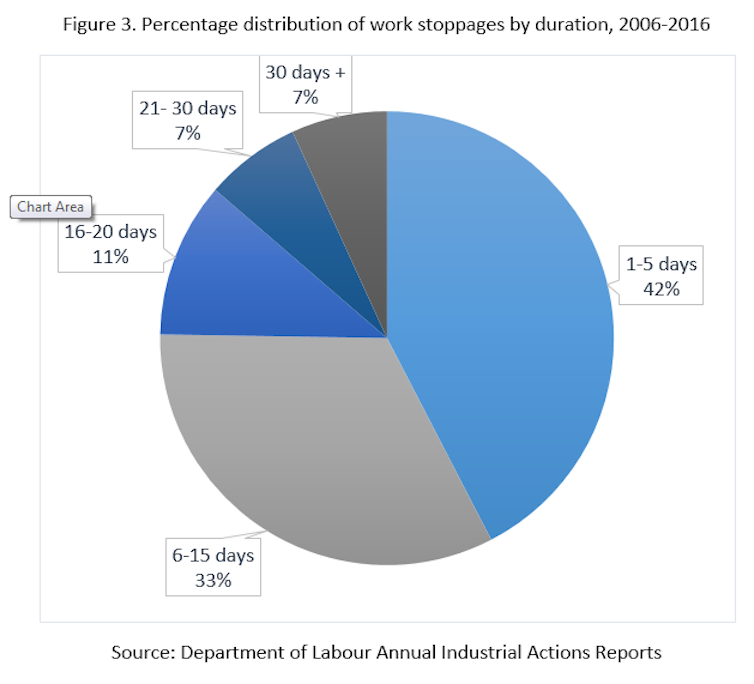

The data also demonstrates that strikes in South Africa don’t tend to be prolonged. In the last decade nearly three quarters of strikes were resolved within two weeks; 42% were resolved in less than a week. Only a very small proportion – 6.8% – last for more than a month.

Department of Labour Annual Industrial Actions Reports

But some may argue that South Africa’s levels of strike activity is unacceptably high in comparison to other countries. Again, this is not borne out in the data.

Researchers from the University of Cape Town, Haroon Bhorat and David Tseng, did comparative analysis looking at two measures: the depth of strike activity (the number of working days lost per strikers’ working days per annum) and strikers’ intensity (the number of strikers per 1,000 employed workers). They found that South Africa’s depth of strike activity was lower than a number of countries including the United States, Brazil and India.

They also found that South Africa’s strikers’ intensity was comparable to a number of European states, among them Austria, Finland and Denmark. It was much lower than countries such as Argentina, Spain and Italy. This means that South Africa’s levels of industrial action are comparable to or even lower than many other middle- and upper-income countries.

Violent vs orderly strikes

Finally, there is the question of strike violence. To date, there has been little attempt to quantify levels of strike violence. Often analysts rely on media reports, including analysis done by the South African Institute for Race Relations, a think-tank who publishes research designed to assist policymakers.

But media data has an inherent bias towards the reporting of violent incidents and so can’t be used as a basis to generalise to all strikes.

A much better source, although not without its limitations, is data collected by Public Order Policing in the Incident Registration Information System which counts crowd management incidents, referring to any incident where it might be necessary to manage a crowd.

This includes large funerals, cultural events, sporting events as well as community protests and strikes. Examining this data, which I did as part of a team at the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Social Change, provides important insights into the nature of strike violence.

We analysed a large representative sample of labour-related protests between 1997 and 2013. The vast majority – 88% – were orderly.

While incidents of violence during strikes should be taken seriously, it is also important to understand them in proportion to their frequency.

The Labour Relations Act is the cornerstone of South Africa’s industrial relations framework. Amendments to it should be based on robust evidence.

This story first appeared on The Conversation

South Africa Today – Business

![]()